- Plot And Theme 2nd Grade

- Plot And Theme

- Examples Of Plot Events

- Plot And Theme Activities

- Plot And Theme Worksheets

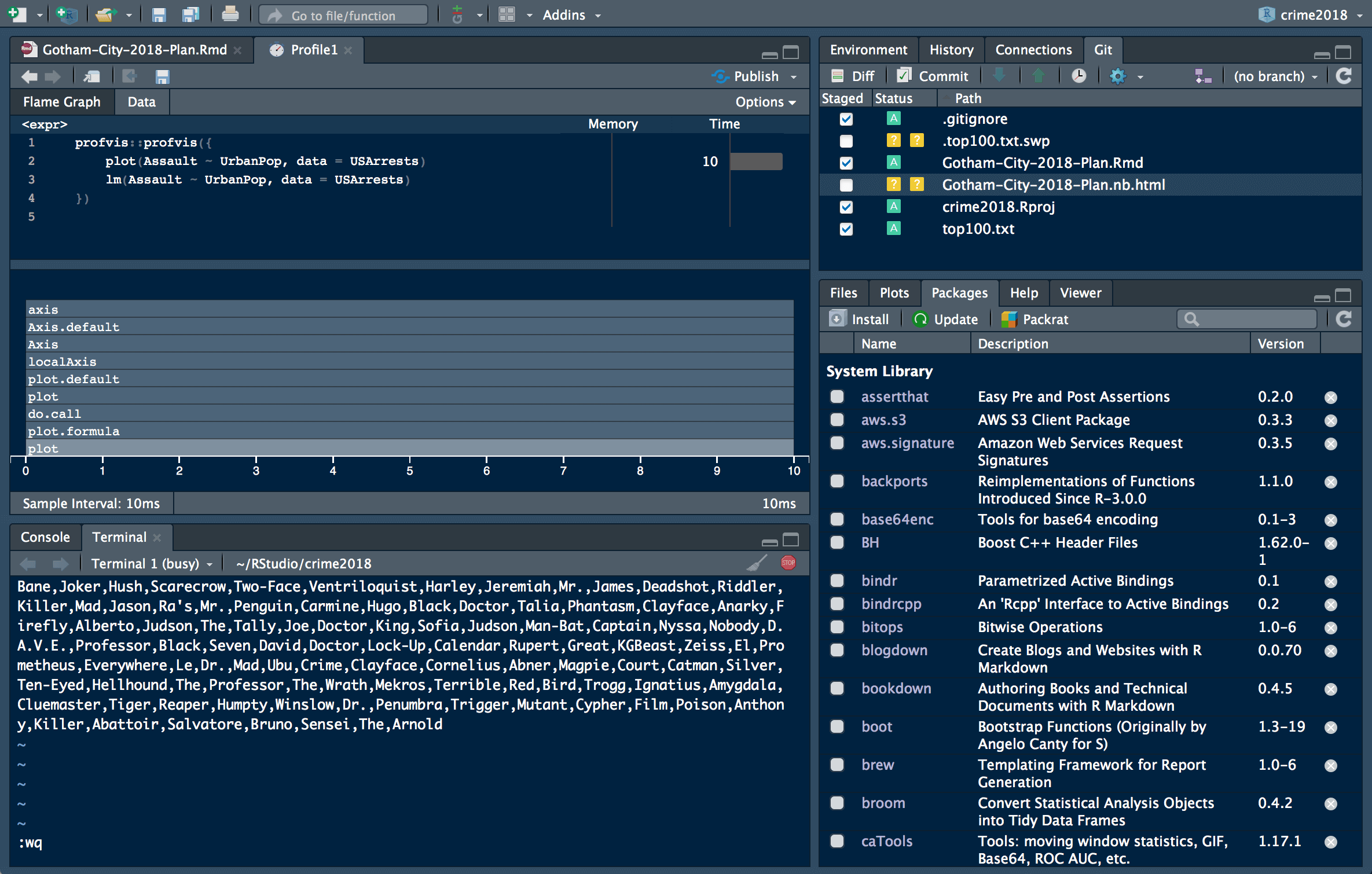

The theme is a common idea that is incorporated and repeated throughout a literary work. A theme is often also called “the moral of the story.” The author uses the characters, plot, and other literary devices to build and enhance the theme. The theme weaves through the entire story and is highlighted by symbols, setting and character actions. As well as applying themes a plot at a time, you can change the default theme with themeset. For example, if you really hate the default grey background, run themeset(themebw) to use a white background for all plots. You’re not limited to the themes built-in to ggplot2. Other packages, like ggthemes by Jeffrey Arnold, add even more.

- Customize the appearance of the plot background

- Use a custom theme

This R tutorial describes how to change the look of a plot theme (background color, panel background color and grid lines) using R software and ggplot2 package. You’ll also learn how to use the base themes of ggplot2 and to create your own theme.

Related Book:

GGPlot2 Essentials for Great Data Visualization in R

ToothGrowth data is used :

Make sure that the variable dose is converted as a factor using the above R script.

Several functions are available in ggplot2 package for changing quickly the theme of plots :

- theme_gray : gray background color and white grid lines

- theme_bw : white background and gray grid lines

ggplot2 background color, theme_gray and theme_bw, R programming

- theme_linedraw : black lines around the plot

- theme_light : light gray lines and axis (more attention towards the data)

ggplot2 background color, theme_linedraw and theme_light, R programming

- theme_minimal: no background annotations

- theme_classic : theme with axis lines and no grid lines

ggplot2 background color, theme_minimal and theme_classic, R programming

- theme_void: Empty theme, useful for plots with non-standard coordinates or for drawings

- theme_dark(): Dark background designed to make colours pop out

ggplot2 background color, theme_void and theme_dark, R programming

The functions theme_xx() can take the two arguments below :

- base_size : base font size (to change the size of all plot text elements)

- base_family : base font family

The size of all the plot text elements can be easily changed at once :

ggplot2 background color, font size, R programming

Note that, the function theme_set() changes the theme for the entire session.

The function theme() is used to control non-data parts of the graph including :

- Line elements : axis lines, minor and major grid lines, plot panel border, axis ticks background color, etc.

- Text elements : plot title, axis titles, legend title and text, axis tick mark labels, etc.

- Rectangle elements : plot background, panel background, legend background, etc.

There is a specific function to modify each of these three elements :

- element_line() to modify the line elements of the theme

- element_text() to modify the text elements

- element_rect() to change the appearance of the rectangle elements

Note that, each of the theme elements can be removed using the function element_blank()

Change the colors of the plot panel background and the grid lines

- The functions theme() and element_rect() are used for changing the plot panel background color :

Plot And Theme 2nd Grade

- fill : the fill color for the rectangle

- colour, color : border color

- size : border size

- The appearance of grid lines can be changed using the function element_line() as follow :

- colour, color : line color

- size : line size

- linetype : line type. Line type can be specified using either text (“blank”, “solid”, “dashed”, “dotted”, “dotdash”, “longdash”, “twodash”) or number (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). Note that linetype = “solid” is identical to linetype=1. The available line types in R are described here : Line types in R software

- lineend : line end. Possible values for line end are : “round”, “butt” or “square”

The R code below illustrates how to modify the appearance of the plot panel background and grid lines :

ggplot2 background color, grid lines, R programming

Remove plot panel borders and grid lines

It is possible to hide plot panel borders and grid lines with the function element_blank() as follow :

ggplot2 background color, remove plot panel border, remove grid lines, R programming

Change the plot background color (not the panel)

You can change the entire appearance of a plot by using a custom theme. Jeffrey Arnold has implemented the library ggthemes containing several custom themes.

To use these themes install and load ggthemes package as follow :

ggthemes package provides many custom themes and scales for ggplot.

theme_tufte : a minimalist theme

theme_economist : theme based on the plots in the economist magazine

Note that, the function scale_fill_economist() are also available.

theme_stata: theme based on Stata graph schemes.

The stata theme color scales can be used as follow :

The allowed values for the argument scheme are one of “s2color”, “s1rcolor”, “s1color”, or “mono”.

theme_wsj: theme based on plots in the Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal color and fill scales are :

The color palette to use can be one of “rgby”, “red_green”, “black_green”, “dem_rep”, “colors6”.

theme_calc : theme based on LibreOffice Calc

These themes are based on the defaults in Google Docs and LibreOffice Calc, respectively.

theme_hc : theme based on Highcharts JS

- You can change the theme for the current R session using the function theme_set() as follow :

- You can extract and modify the R code of theme_gray :

Note that, the function rel() modifies the size relative to the base size

This analysis has been performed using R software (ver. 3.2.4) and ggplot2 (ver. 2.1.0)

Show me some love with the like buttons below... Thank you and please don't forget to share and comment below!!

Montrez-moi un peu d'amour avec les like ci-dessous ... Merci et n'oubliez pas, s'il vous plaît, de partager et de commenter ci-dessous!

Recommended for You!

Plot And Theme

More books on R and data science

Recommended for you

This section contains best data science and self-development resources to help you on your path.

Coursera - Online Courses and Specialization

Data science

- Course: Machine Learning: Master the Fundamentals by Standford

- Specialization: Data Science by Johns Hopkins University

- Specialization: Python for Everybody by University of Michigan

- Courses: Build Skills for a Top Job in any Industry by Coursera

- Specialization: Master Machine Learning Fundamentals by University of Washington

- Specialization: Statistics with R by Duke University

- Specialization: Software Development in R by Johns Hopkins University

- Specialization: Genomic Data Science by Johns Hopkins University

Popular Courses Launched in 2020

- Google IT Automation with Python by Google

- AI for Medicine by deeplearning.ai

- Epidemiology in Public Health Practice by Johns Hopkins University

- AWS Fundamentals by Amazon Web Services

Trending Courses

- The Science of Well-Being by Yale University

- Google IT Support Professional by Google

- Python for Everybody by University of Michigan

- IBM Data Science Professional Certificate by IBM

- Business Foundations by University of Pennsylvania

- Introduction to Psychology by Yale University

- Excel Skills for Business by Macquarie University

- Psychological First Aid by Johns Hopkins University

- Graphic Design by Cal Arts

Books - Data Science

Our Books

- Practical Guide to Cluster Analysis in R by A. Kassambara (Datanovia)

- Practical Guide To Principal Component Methods in R by A. Kassambara (Datanovia)

- Machine Learning Essentials: Practical Guide in R by A. Kassambara (Datanovia)

- R Graphics Essentials for Great Data Visualization by A. Kassambara (Datanovia)

- GGPlot2 Essentials for Great Data Visualization in R by A. Kassambara (Datanovia)

- Network Analysis and Visualization in R by A. Kassambara (Datanovia)

- Practical Statistics in R for Comparing Groups: Numerical Variables by A. Kassambara (Datanovia)

- Inter-Rater Reliability Essentials: Practical Guide in R by A. Kassambara (Datanovia)

Others

- R for Data Science: Import, Tidy, Transform, Visualize, and Model Data by Hadley Wickham & Garrett Grolemund

- Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems by Aurelien Géron

- Practical Statistics for Data Scientists: 50 Essential Concepts by Peter Bruce & Andrew Bruce

- Hands-On Programming with R: Write Your Own Functions And Simulations by Garrett Grolemund & Hadley Wickham

- An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R by Gareth James et al.

- Deep Learning with R by François Chollet & J.J. Allaire

- Deep Learning with Python by François Chollet

Want to Learn More on R Programming and Data Science?

Follow us by EmailOn Social Networks:

Click to follow us on Facebook and Google+ :

Comment this article by clicking on 'Discussion' button (top-right position of this page)

18.1 Introduction

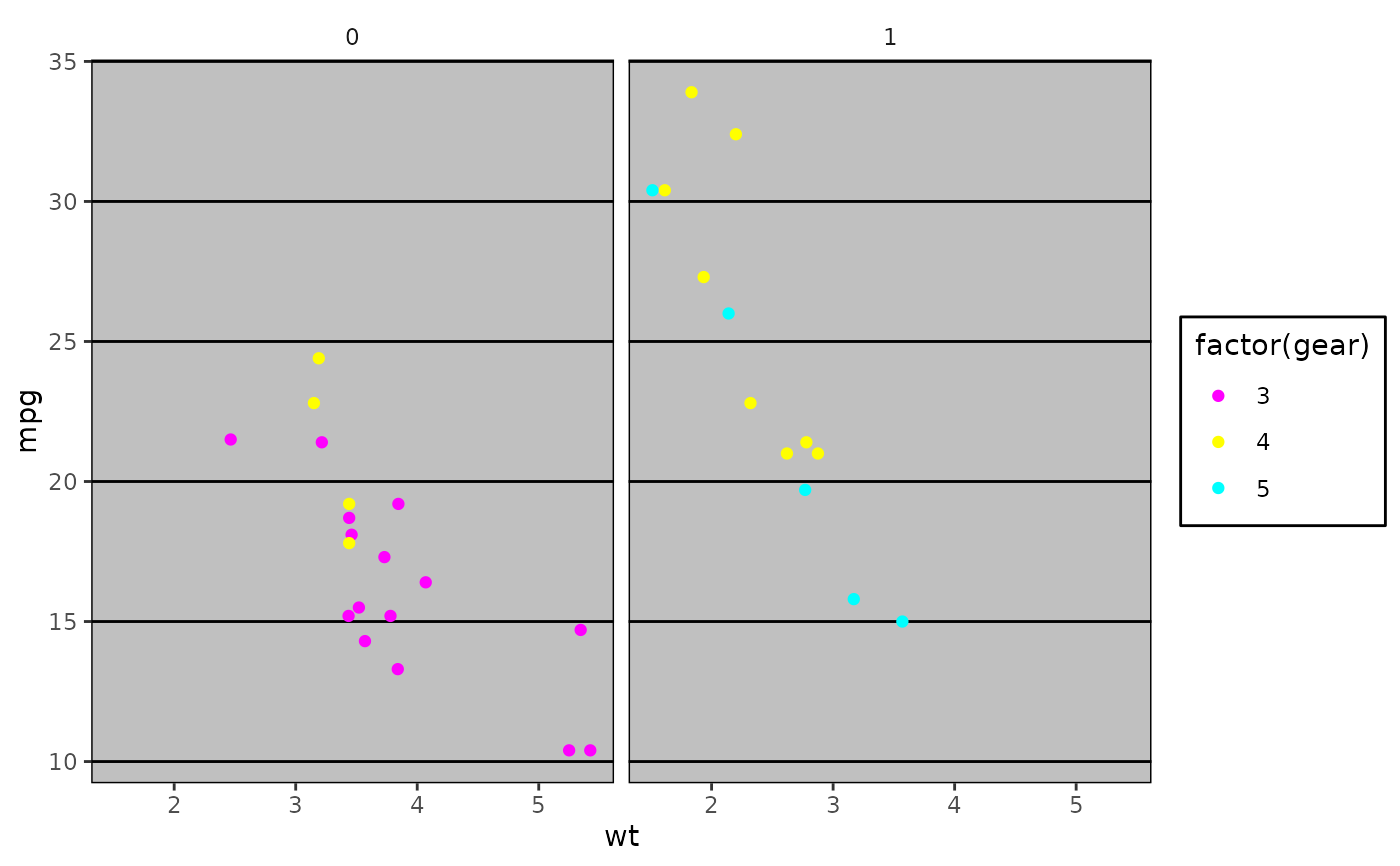

In this chapter you will learn how to use the ggplot2 theme system, which allows you to exercise fine control over the non-data elements of your plot. The theme system does not affect how the data is rendered by geoms, or how it is transformed by scales. Themes don’t change the perceptual properties of the plot, but they do help you make the plot aesthetically pleasing or match an existing style guide. Themes give you control over things like fonts, ticks, panel strips, and backgrounds.

This separation of control into data and non-data parts is quite different from base and lattice graphics. In base and lattice graphics, most functions take a large number of arguments that specify both data and non-data appearance, which makes the functions complicated and harder to learn. ggplot2 takes a different approach: when creating the plot you determine how the data is displayed, then after it has been created you can edit every detail of the rendering, using the theming system.

The theming system is composed of four main components:

Theme elements specify the non-data elements that you can control.For example, the

plot.titleelement controls the appearance of theplot title;axis.ticks.x, the ticks on the x axis;legend.key.height,the height of the keys in the legend.Each element is associated with an element function, which describesthe visual properties of the element. For example,

element_text()setsthe font size, colour and face of text elements likeplot.title.The

theme()function which allows you to override the default themeelements by calling element functions, liketheme(plot.title = element_text(colour = 'red')).Complete themes, like

theme_grey()set all of the theme elements tovalues designed to work together harmoniously.

For example, imagine you’ve made the following plot of your data.

Examples Of Plot Events

It’s served its purpose for you: you’ve learned that cty and hwy are highly correlated, both are tightly coupled with cyl, and that hwy is always greater than cty (and the difference increases as cty increases). Now you want to share the plot with others, perhaps by publishing it in a paper. That requires some changes. First, you need to make sure the plot can stand alone by:

- Improving the axes and legend labels.

- Adding a title for the plot.

- Tweaking the colour scale.

Fortunately you know how to do that already because you’ve read Section 8.1 and Chapter (scale-colour):

Next, you need to make sure the plot matches the style guidelines of your journal:

- The background should be white, not pale grey.

- The legend should be placed inside the plot if there’s room.

- Major gridlines should be a pale grey and minor gridlines should be removed.

- The plot title should be 12pt bold text.

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to use the theming system to make those changes, as shown below:

Finally, the journal wants the figure as a 600 dpi TIFF file. You’ll learn the fine details of ggsave() in Section 18.5.

18.2 Complete themes

ggplot2 comes with a number of built in themes. The most important is theme_grey(), the signature ggplot2 theme with a light grey background and white gridlines. The theme is designed to put the data forward while supporting comparisons, following the advice of.Edward R. Tufte, Beautiful Evidence (Graphics Press, 2006); Cynthia A. Brewer, “Color Use Guidelines for Mapping and Visualization,” in Visualization in Modern Cartography, ed. A. M. MacEachren and D. R. F. Taylor (Elsevier Science, 1994), 123–47; Dan Carr, “Graphical Displays,” in Encyclopedia of Environmetrics, ed. Abdel H. El-Shaarawi and Walter W. Piegorsch, vol. 2 (John Wiley & Sons, 2002), 933–60, http://www.galaxy.gmu.edu/~dcarr/lib/EnvironmentalGraphics.pdf; Dan Carr, “Using Gray in Plots,” ASA Statistical Computing and Graphics Newsletter 2, no. 5 (1994): 11–14, http://www.galaxy.gmu.edu/~dcarr/lib/v5n2.pdf; Dan Carr and Ru Sun, “Using Layering and Perceptual Grouping in Statistical Graphics,” ASA Statistical Computing and Graphics Newsletter 10, no. 1 (1999): 25–31.

There are seven other themes built in to ggplot2 1.1.0:

theme_bw(): a variation ontheme_grey()that uses a white backgroundand thin grey grid lines.theme_linedraw(): A theme with only black lines of various widths on whitebackgrounds, reminiscent of a line drawing.theme_light(): similar totheme_linedraw()but with light grey lines andaxes, to direct more attention towards the data.theme_dark(): the dark cousin oftheme_light(), with similar line sizesbut a dark background. Useful to make thin coloured lines pop out.theme_minimal(): A minimalistic theme with no background annotations.theme_classic(): A classic-looking theme, with x and y axis lines and nogridlines.theme_void(): A completely empty theme.

All themes have a base_size parameter which controls the base font size. The base font size is the size that the axis titles use: the plot title is usually bigger (1.2x), and the tick and strip labels are smaller (0.8x). If you want to control these sizes separately, you’ll need to modify the individual elements as described below.

As well as applying themes a plot at a time, you can change the default theme with theme_set(). For example, if you really hate the default grey background, run theme_set(theme_bw()) to use a white background for all plots.

You’re not limited to the themes built-in to ggplot2. Other packages, like ggthemes by Jeffrey Arnold, add even more. Here’s a few of my favourites from ggthemes:

The complete themes are a great place to start but don’t give you a lot of control. To modify individual elements, you need to use theme() to override the default setting for an element with an element function.

18.2.1 Exercises

Try out all the themes in ggthemes. Which do you like the best?

What aspects of the default theme do you like? What don’t you like?

What would you change?Look at the plots in your favourite scientific journal. What themedo they most resemble? What are the main differences?

18.3 Modifying theme components

To modify an individual theme component you use code like plot + theme(element.name = element_function()). In this section you’ll learn about the basic element functions, and then in the next section, you’ll see all the elements that you can modify.

There are four basic types of built-in element functions: text, lines, rectangles, and blank. Each element function has a set of parameters that control the appearance:

element_text()draws labels and headings. You can control the fontfamily,face,colour,size(in points),hjust,vjust,angle(in degrees) andlineheight(as ratio offontcase). More details onthe parameters can be found invignette('ggplot2-specs').Setting the font face is particularly challenging.You can control the margins around the text with the

marginargument andmargin()function.margin()has four arguments: the amount of space(in points) to add to the top, right, bottom and left sides of the text.Any elements not specified default to 0.element_line()draws lines parameterised bycolour,sizeandlinetype:element_rect()draws rectangles, mostly used for backgrounds, parameterisedbyfillcolour and bordercolour,sizeandlinetype.element_blank()draws nothing. Use this if you don’t want anything drawn,and no space allocated for that element. The following example useselement_blank()to progressively suppress the appearance of elementswe’re not interested in. Notice how the plot automatically reclaimsthe space previously used by these elements: if you don’t want this tohappen (perhaps because they need to line up with other plots on the page),usecolour = NA, fill = NAto create invisible elements thatstill take up space.A few other settings take grid units. Create them with

unit(1, 'cm')orunit(0.25, 'in').

To modify theme elements for all future plots, use theme_update(). It returns the previous theme settings, so you can easily restore the original parameters once you’re done.

18.4 Theme elements

There are around 40 unique elements that control the appearance of the plot. They can be roughly grouped into five categories: plot, axis, legend, panel and facet. The following sections describe each in turn.

18.4.1 Plot elements

Some elements affect the plot as a whole:

| Element | Setter | Description |

|---|---|---|

| plot.background | element_rect() | plot background |

| plot.title | element_text() | plot title |

| plot.margin | margin() | margins around plot |

plot.background draws a rectangle that underlies everything else on the plot. By default, ggplot2 uses a white background which ensures that the plot is usable wherever it might end up (e.g. even if you save as a png and put on a slide with a black background). When exporting plots to use in other systems, you might want to make the background transparent with fill = NA. Similarly, if you’re embedding a plot in a system that already has margins you might want to eliminate the built-in margins. Note that a small margin is still necessary if you want to draw a border around the plot.

18.4.2 Axis elements

The axis elements control the apperance of the axes:

| Element | Setter | Description |

|---|---|---|

| axis.line | element_line() | line parallel to axis (hidden in default themes) |

| axis.text | element_text() | tick labels |

| axis.text.x | element_text() | x-axis tick labels |

| axis.text.y | element_text() | y-axis tick labels |

| axis.title | element_text() | axis titles |

| axis.title.x | element_text() | x-axis title |

| axis.title.y | element_text() | y-axis title |

| axis.ticks | element_line() | axis tick marks |

| axis.ticks.length | unit() | length of tick marks |

Note that axis.text (and axis.title) comes in three forms: axis.text, axis.text.x, and axis.text.y. Use the first form if you want to modify the properties of both axes at once: any properties that you don’t explicitly set in axis.text.x and axis.text.y will be inherited from axis.text.

The most common adjustment is to rotate the x-axis labels to avoid long overlapping labels. If you do this, note negative angles tend to look best and you should set hjust = 0 and vjust = 1:

18.4.3 Legend elements

The legend elements control the apperance of all legends. You can also modify the appearance of individual legends by modifying the same elements in guide_legend() or guide_colourbar().

| Element | Setter | Description |

|---|---|---|

| legend.background | element_rect() | legend background |

| legend.key | element_rect() | background of legend keys |

| legend.key.size | unit() | legend key size |

| legend.key.height | unit() | legend key height |

| legend.key.width | unit() | legend key width |

| legend.margin | unit() | legend margin |

| legend.text | element_text() | legend labels |

| legend.text.align | 0–1 | legend label alignment (0 = right, 1 = left) |

| legend.title | element_text() | legend name |

| legend.title.align | 0–1 | legend name alignment (0 = right, 1 = left) |

These options are illustrated below:

There are four other properties that control how legends are laid out in the context of the plot (legend.position, legend.direction, legend.justification, legend.box). They are described in Section 11.6.1.

18.4.4 Panel elements

Panel elements control the appearance of the plotting panels:

| Element | Setter | Description |

|---|---|---|

| panel.background | element_rect() | panel background (under data) |

| panel.border | element_rect() | panel border (over data) |

| panel.grid.major | element_line() | major grid lines |

| panel.grid.major.x | element_line() | vertical major grid lines |

| panel.grid.major.y | element_line() | horizontal major grid lines |

| panel.grid.minor | element_line() | minor grid lines |

| panel.grid.minor.x | element_line() | vertical minor grid lines |

| panel.grid.minor.y | element_line() | horizontal minor grid lines |

| aspect.ratio | numeric | plot aspect ratio |

The main difference between panel.background and panel.border is that the background is drawn underneath the data, and the border is drawn on top of it. For that reason, you’ll always need to assign fill = NA when overriding panel.border.

Note that aspect ratio controls the aspect ratio of the panel, not the overall plot:

18.4.5 Faceting elements

The following theme elements are associated with faceted ggplots:

| Element | Setter | Description |

|---|---|---|

| strip.background | element_rect() | background of panel strips |

| strip.text | element_text() | strip text |

| strip.text.x | element_text() | horizontal strip text |

| strip.text.y | element_text() | vertical strip text |

| panel.margin | unit() | margin between facets |

| panel.margin.x | unit() | margin between facets (vertical) |

| panel.margin.y | unit() | margin between facets (horizontal) |

Element strip.text.x affects both facet_wrap() or facet_grid(); strip.text.y only affects facet_grid().

18.4.6 Exercises

Create the ugliest plot possible! (Contributed by Andrew D. Steen,University of Tennessee - Knoxville)

theme_dark()makes the inside of the plot dark, but not theoutside. Change the plot background to black, and then update thetext settings so you can still read the labels.Make an elegant theme that uses “linen” as the background colour anda serif font for the text.

Systematically explore the effects of

hjustwhen you have a multilinetitle. Why doesn’tvjustdo anything?

18.5 Saving your output

When saving a plot to use in another program, you have two basic choices of output: raster or vector:

Plot And Theme Activities

Vector graphics describe a plot as sequence of operations: draw a linefrom ((x_1, y_1)) to ((x_2, y_2)), draw a circle at ((x_3, x_4)) withradius (r). This means that they are effectively ‘infinitely’ zoomable;there is no loss of detail. The most useful vector graphic formats arepdf and svg.

Raster graphics are stored as an array of pixel colours and have a fixedoptimal viewing size. The most useful raster graphic format is png.

Figure 18.1 illustrates the basic differences in these formats for a circle. A good description is available at http://tinyurl.com/rstrvctr.

Figure 18.1: The schematic difference between raster (left) and vector (right) graphics.

Unless there is a compelling reason not to, use vector graphics: they look better in more places. There are two main reasons to use raster graphics:

You have a plot (e.g. a scatterplot) with thousands of graphical objects(i.e. points). A vector version will be large and slow to render.

You want to embed the graphic in MS Office. MS has poor support for vectorgraphics (except for their own DrawingXML format which is not currentlyeasy to make from R), so raster graphics are easier.

There are two ways to save output from ggplot2. You can use the standard R approach where you open a graphics device, generate the plot, then close the device:

This works for all packages, but is verbose. ggplot2 provides a convenient shorthand with ggsave():

ggsave() is optimised for interactive use: you can use it after you’ve drawn a plot. It has the following important arguments:

The first argument,

path, specifies the path where the image should besaved. The file extension will be used to automatically select the correctgraphics device.ggsave()can produce.eps,.pdf,.svg,.wmf,.png,.jpg,.bmp, and.tiff.widthandheightcontrol the output size, specified in inches. If leftblank, they’ll use the size of the on-screen graphics device.For raster graphics (i.e.

.png,.jpg), thedpiargument controls theresolution of the plot. It defaults to 300, which is appropriate for mostprinters, but you may want to use 600 for particularly high-resolution output,or 96 for on-screen (e.g., web) display.

Plot And Theme Worksheets

See ?ggsave for more details.