Figuring these 8 plot points ahead of time will also make writing your screenplay a thousand times easier. But in my already lengthy post, I didn’t have time to include examples. So today, I’m going to use the first of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Fellowship of the Ring, to give examples of the 8 essential plot points. Calculus: Integral with adjustable bounds. Calculus: Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.

In my previous post, How to Write a Script Outline: the 8 Major Plot Points, I described the 8 plot points that can be found in basically EVERY movie. So it makes sense for you to spend a significant chunk of time thinking about them when you write a script outline. Figuring these 8 plot points ahead of time will also make writing your screenplay a thousand times easier.

But in my already lengthy post, I didn’t have time to include examples. So today, I’m going to use the first of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Fellowship of the Ring, to give examples of the 8 essential plot points. Some of you might not have seen Lord of the Rings, *gasp* so I’m going to describe people and places you might not be familiar with. For everyone who has seen it (the majority I bet), please excuse the clarifications. Here’s the link again, in case you want a refresher of the 8 plot points you need to think about before you write a script outline.

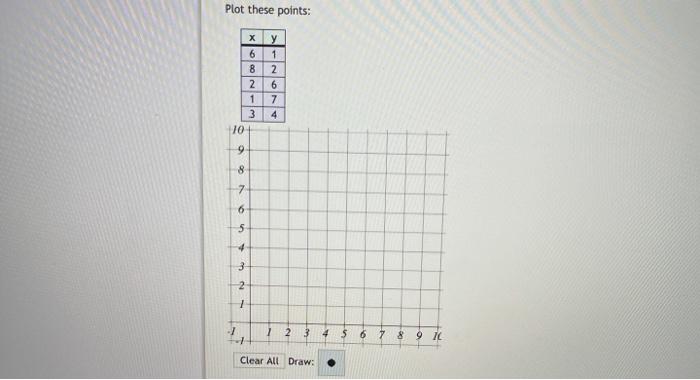

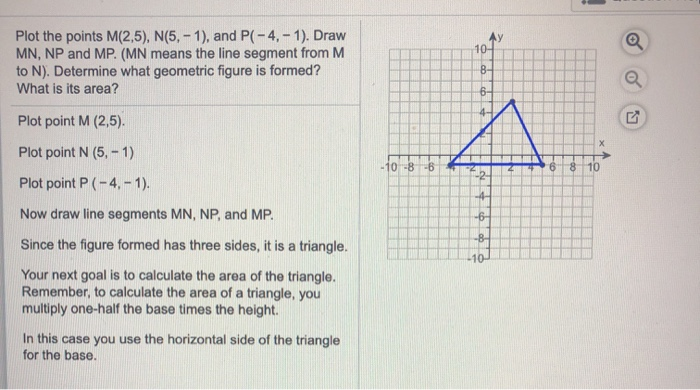

- Plot Points - Displaying top 8 worksheets found for this concept. Some of the worksheets for this concept are Plotting coordinate points a, 3 points in the coordinate, Plotting points positive s1, Plotting points, Line plots, Grade 4 geometry work, Plotting coordinate points d, Day 1 lesson and work.

- Plotting just one novel is challenging, never mind plotting a multi-book arc. Having structure and a plan helps. Here’s how to plot a series in 8, structured steps: 1: Find your ‘Central Idea’ 2: Find key plot points for each book in your series 3: List ideas for your series’ end goal 4: Decide on the broad setting of your series.

Plot Point #1: Opening & Closing Images

The first image in the Fellowship of the Ring is a picture of a smoldering crucible. (A crucible is just a nifty container you can melt metal in.)

The goal of our hobbit hero, Frodo, is to destroy the One Ring in the fires of Mordor, turning it into molten metal again. That’s why this opening image is so perfect. It symbolizes the entire goal and journey of the main character.

From the get-go, Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens & Peter Jackson showed us how skillfully they adapted such a treasured literary work. No wonder they nabbed so many Oscars. (Remember this if you’re also interested in adaptations.)

The closing image is of Frodo and his sidekick, Sam, rowing off to face the next part of their journey. This image isn’t as powerful as the opening one, but it serves its purpose: it indicates that Frodo and Sam haven’t finished their journey, but whatever evil they’ll encounter next, they’ll face it together.

So the closing image makes a statement about the power of friendship, one of the recurring themes in the LOTR trilogy. It also makes us curious to see if they’ll succeed…whetting our appetite for the next installment.

Plot Point #2: Inciting Incident

Frodo, our hero, is going about his business in the Shire, where all the hobbits live. (For those of you unfamiliar with hobbits, they’re little people who live in a network of burrows. They’re generally peaceful and not materialistic.)

And his life would’ve continued as usual…if his uncle Bilbo hadn’t decided to leave the Shire and give the One Ring to Frodo. Once the ring enters Frodo’s life, it utterly changes his destiny. Instead of idle days smoking pipe-weed, Frodo will instead face danger and pain. Click on this link for more examples of inciting incidents.

Plot Point #3: First Act Break

Naturally, Frodo isn’t keen to embrace this responsibility. The great wizard Gandalf finally convinces Frodo that he must at least take the ring out of the Shire.

When Frodo leaves, he is joined by his best friend, Sam, and two other hobbits, Pippin and Merry. In this first act break, we see the beginnings of the fellowship, although it’s not yet in its full form. Note too, that the first act break involves a physical location shift — the hobbits must leave the Shire behind and venture into the more dangerous parts of Middle-Earth.

Plot Point #4: the Midpoint

At the midpoint of the Fellowship of the Ring, Frodo volunteers to bear the ring to the fires of Mordor. This shifts the story in two different major ways.

First, this is a HUGE responsibility that Frodo didn’t foresee when he left the Shire. At this midpoint, Frodo becomes less reactive (Bilbo foisted the ring onto Frodo) and more active (he volunteers to go on the next part of the journey).

It also marks the FULL formation of the fellowship as the group of hobbits & Gandalf are joined by an elf, a dwarf, and two men.

This is actually a risky maneuver, as in most adventure stories, we’re introduced to the cast of heroes by the first act break. Keep that in mind when you’re writing your own script outline. LOTR benefited from its history as a literary masterpiece and could take risks that, more likely than not, would not go over well in a spec screenplay.

Plot Point #5: the Point of Commitment

Frodo is tempted to give up the enormous burden of the ring…and he might’ve…if he hadn’t met a powerful elf-queen named Lady Galadriel.

In a magical pool of water, she shows him what life in the Shire would be like if he fails — everything green is burnt and the hobbits are no longer free, just slaves chained together. Because of this, for the first time Frodo realizes that he MUST destroy the ring or die trying. If he doesn’t at least try, there’s 0% chance of anyone in Middle-Earth having a life worth living.

Note: in this movie, the point of commitment occurs after the moment all is lost. Remember, there are no hard and fast rules!

Plot Point #6: All Is Lost

In this all is lost moment, the whip of a Balrog (a fiery demon) drags Gandalf down with him. As a powerful wizard, Gandalf’s loss is significant — it’s like the Jackson 5 losing Michael.

Without Gandalf’s help, the fellowship seems farthest away from success. The emotional intensity of the moment is heightened because of what happened right before it.

Gandalf knew about the Balrog and feared that he wouldn’t have the strength to protect the others from the demon. However, despite his self-doubt, Gandalf does face off against the Balrog — and win. It’s a lovely moment of victory, an emotional high for the whole fellowship.

Just when they think they’ve succeeded, the Balrog’s whip snakes up and hooks around Gandalf. This moment of sadness is made more intense because of the intensity of the positive moment before it. When you’re writing a script outline, you can apply this technique too: heighten the intensity of the emotional lows by preceding them with really positive highs.

Plot Point #7: the Climax

In the climax, the Uruk-hai, henchmen of an evil wizard, catch up with the fellowship. A massive battle follows. The fellowship demonstrates their courage. One of the men, Boromir, who seemed the most likely to betray Frodo, redeems himself. Ultimately, he sacrifices his life to enable Frodo’s escape.

Plot Point #8: the Resolution

Unfortunately for Frodo, the Lord of the Rings has three parts, so he doesn’t get to enjoy the fruits of his labor. He has another journey to begin — and he will do so with his trusty sidekick, Sam. While the fellowship has splintered into different groups, hope is still strong.

Frodo and Same: In It Till THE END

Final thoughts

I hope these examples from the Fellowship of the Ring aid your understanding of the 8 essential plot points every screenplay — and script outline — needs. You have no more excuses if you haven’t yet seen LOTR, so rent it now.

If you want to develop your plotting intuition, make it a regular practice to identify the 8 plot points in ALL the movies you watch.

Another great method: take the plot points of various blockbuster movies I post each Thursday, put them onto index cards, and arrange them into columns, making sure the bottom card of each column is a key turning point in the story.

Do this often enough, and writing a script outline will be a breeze.

Gold Ring by Derek Gavey

| Author | Christopher Booker |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Published | 2004 |

| Pages | 736 |

| Preceded by | The Great Deception |

| Followed by | Scared to Death: From BSE to Global Warming |

The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories is a 2004 book by Christopher Booker containing a Jung-influenced analysis of stories and their psychological meaning. Booker worked on the book for thirty-four years.[1]

Summary[edit]

The meta-plot[edit]

The meta-plot begins with the anticipation stage, in which the hero is called to the adventure to come. This is followed by a dream stage, in which the adventure begins, the hero has some success, and has an illusion of invincibility. However, this is then followed by a frustration stage, in which the hero has his first confrontation with the enemy, and the illusion of invincibility is lost. This worsens in the nightmare stage, which is the climax of the plot, where hope is apparently lost. Finally, in the resolution, the hero overcomes his burden against the odds.

The key thesis of the book: 'However many characters may appear in a story, its real concern is with just one: its hero. It is the one whose fate we identify with, as we see them gradually developing towards that state of self-realization which marks the end of the story. Ultimately it is in relation to this central figure that all other characters in a story take on their significance. What each of the other characters represents is really only some aspect of the inner state of the hero himself.'

The plots[edit]

Overcoming the Monster[edit]

Definition: The protagonist sets out to defeat an antagonistic force (often evil) which threatens the protagonist and/or protagonist's homeland.

8 Plot Points

Examples: Perseus, Theseus, Beowulf, Dracula, The War of the Worlds, Nicholas Nickleby, The Guns of Navarone, Seven Samurai (The Magnificent Seven), James Bond, Jaws, Star Wars, Attack on Titan.

Rags to Riches[edit]

Definition: The poor protagonist acquires power, wealth, and/or a mate, loses it all and gains it back, growing as a person as a result.

Teaching Plot Powerpoint

Examples: Cinderella, Aladdin, Jane Eyre, A Little Princess, Great Expectations, David Copperfield, The Prince and the Pauper, Brewster's Millions. The Jerk.

The Quest[edit]

Definition: The protagonist and companions set out to acquire an important object or to get to a location. They face temptations and other obstacles along the way.

Examples: The Iliad, The Pilgrim's Progress, The Lord Of The Rings, King Solomon's Mines, Six of Crows, Watership Down, Lightning Thief, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

Voyage and Return[edit]

Definition: The protagonist goes to a strange land and, after overcoming the threats it poses or learning important lessons unique to that location, they return with experience.

Examples: Ramayana, Odyssey, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Orpheus, The Time Machine, Peter Rabbit, The Hobbit, Brideshead Revisited, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Gone with the Wind, The Third Man, The Lion King, Back to the Future, The Midnight Gospel.

Comedy[edit]

8 Plot Points

Definition: Light and humorous character with a happy or cheerful ending; a dramatic work in which the central motif is the triumph over adverse circumstance, resulting in a successful or happy conclusion.[2]Booker stresses that comedy is more than humor. It refers to a pattern where the conflict becomes more and more confusing, but is at last made plain in a single clarifying event. The majority of romance films fall into this category.

Examples: A Midsummer Night's Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Twelfth Night, Bridget Jones's Diary, Music and Lyrics, Sliding Doors, Four Weddings and a Funeral, The Big Lebowski.

Tragedy[edit]

Definition: The protagonist is a hero with a major character flaw or great mistake which is ultimately their undoing. Their unfortunate end evokes pity at their folly and the fall of a fundamentally good character.

Examples: Anna Karenina, Bonnie and Clyde, Carmen, Citizen Kane, John Dillinger, Jules et Jim, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Madame Bovary, Oedipus Rex, The Picture of Dorian Gray, Romeo and Juliet.

Rebirth[edit]

Definition: An event forces the main character to change their ways and often become a better individual.

Examples: Pride and Prejudice, The Frog Prince, Beauty and the Beast, The Snow Queen, A Christmas Carol, The Secret Garden, Peer Gynt, Groundhog Day.

The Rule of Three[edit]

'Again and again, things appear in threes . . .' There is rising tension and the third event becomes 'the final trigger for something important to happen'. We are accustomed to this pattern from childhood stories such as Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Cinderella, and Little Red Riding Hood. In adult stories, three can convey the gradual working out of a process that leads to transformation. This transformation can be downwards as well as upwards.Booker asserts that the Rule of Three is expressed in four ways:

- The simple, or cumulative three, for example, Cinderella's three visits to the ball.

- The ascending three, where each event is of more significance than the preceding, for example, the hero must win first bronze, then silver, then gold objects.

- The contrasting three, where only the third has positive value, for example, The Three Little Pigs, two of whose houses are blown down by the Big Bad Wolf.

- The final or dialectical form of three, where, as with Goldilocks and her bowls of porridge, the first is wrong in one way, the second in an opposite way, and the third is 'just right'. [3]

Precursors[edit]

- William Foster-Harris' The Basic Patterns of Plot sets out a theory of three basic patterns of plot.[4]

- Ronald B. Tobias set out a twenty-plot theory in his 20 Master Plots.[4]

- Georges Polti's The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations.[4]

- Several of these plots can also be seen as reworkings of Joseph Campbell's work on the quest and return in The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Reception[edit]

Scholars and journalists have had mixed responses to The Seven Basic Plots. Some have celebrated the book's audacity and breadth. The author and essayist Fay Weldon, for example, wrote the following (which is quoted on the front cover of the book): 'This is the most extraordinary, exhilarating book. It always seemed to me that 'the story' was God's way of giving meaning to crude creation. Booker now interprets the mind of God, and analyses not just the novel – which will never to me be quite the same again – but puts the narrative of contemporary human affairs into a new perspective. If it took its author a lifetime to write, one can only feel gratitude that he did it.'[5]Beryl Bainbridge, Richard Adams, Ronald Harwood, and John Bayley also spoke positively of the work, while philosopher Roger Scruton described it as a 'brilliant summary of story-telling'.[6]

8 Plot Points Screenwriting

Others have dismissed the book, criticizing especially Booker's normative conclusions. Novelist and literary critic Adam Mars-Jones, for instance, wrote, 'He sets up criteria for art, and ends up condemning Rigoletto, The Cherry Orchard, Wagner, Proust, Joyce, Kafka and Lawrence—the list goes on—while praising Crocodile Dundee, E.T. and Terminator 2'.[7] Similarly, Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times writes, 'Mr. Booker evaluates works of art on the basis of how closely they adhere to the archetypes he has so laboriously described; the ones that deviate from those classic patterns are dismissed as flawed or perverse – symptoms of what has gone wrong with modern art and the modern world.'[8]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^'Terminator 2 good, The Odyssey bad'. The Guardian. 2004-11-21. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^'the definition of comedy'. Dictionary.com.

- ^Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots, Continuum 2006, p 229-233

- ^ abc'The 'Basic' Plots in Literature'. Archived from the original on 2015-08-21. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ^'The Seven Basic Plots'. Bloomsbury. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ^Scruton, Roger (February 2005). 'Wagner: moralist or monster?'. The New Criterion. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^Adam Mars-Jones 'Terminator 2 Good, The Odyssey Bad', The Observer, November 21, 2004, retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^Kakutani, Michiko (2005-04-15). 'The Plot Thins, or Are No Stories New?'. The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-09-11.